I’ve never loved taking tests.

Growing up, I went to a school that did not administer any tests or letter grades — we spent a lot of time doing watercolor illustrations of our lessons and received holistic feedback at the end of the year in the hopes of fostering our “love of learning” (if this is ringing a bell for anyone, yes, I went to a Waldorf school).

I had a great time but did not get much exposure to the pressure and stress of test-taking. I’ve never quite gotten used to it.

The French education system is entirely the opposite.

Tests are the primordial. Everything is graded on a scale of 1 to 20, 10 counting as passing. 12 counts as ‘pretty good’ and 14 as ‘good.’ Earning a 16 is rare and warrants a ‘very good’ mention on your diploma. Anything under a 10, and you have to take the exam over again or risk repeating the entire year.

Perfection does not exist; the French are realists and do not try to inflate egos with generous grades.

I’ll admit that when I signed up for culinary school, I hadn’t understood that we would be tested nearly every month. But I shouldn't have been surprised, as I knew that the year would culminate in a national test in June — but I didn’t know the details.

It turns out that the final exam is no small feat. It will consist of a 3-hour written exam and 5-hour practical exam in the kitchen. In an attempt to prepare us as best as possible, our school organized practice tests last week.

We started with the easy stuff on the first day — the written exam.

This portion covered best practices in kitchen management and health and safety, including questions like “Why do you have to freeze certain wild saltwater fish before serving them raw as tartare or sushi?”

I knew the answer to that one — freezing fish for over 24 hours at -20 degrees celsius (or -4 degrees Fahrenheit) kills the very common anisakis parasite. But it turns out that this particular question was a bad omen. More on that later.

The real zinger was the practical test scheduled the following day. Over the course of 5-ish hours, we were expected to make either a starter (for 8) and a main (for 4) OR a main and a dessert (for 8).

We were given our subjects at the start of the exam and 10 minutes to write down our “plan,” referring to any recipes we’ve noted in our notebooks. We were six to a kitchen, all starting at different times and each with a different duo of recipes.

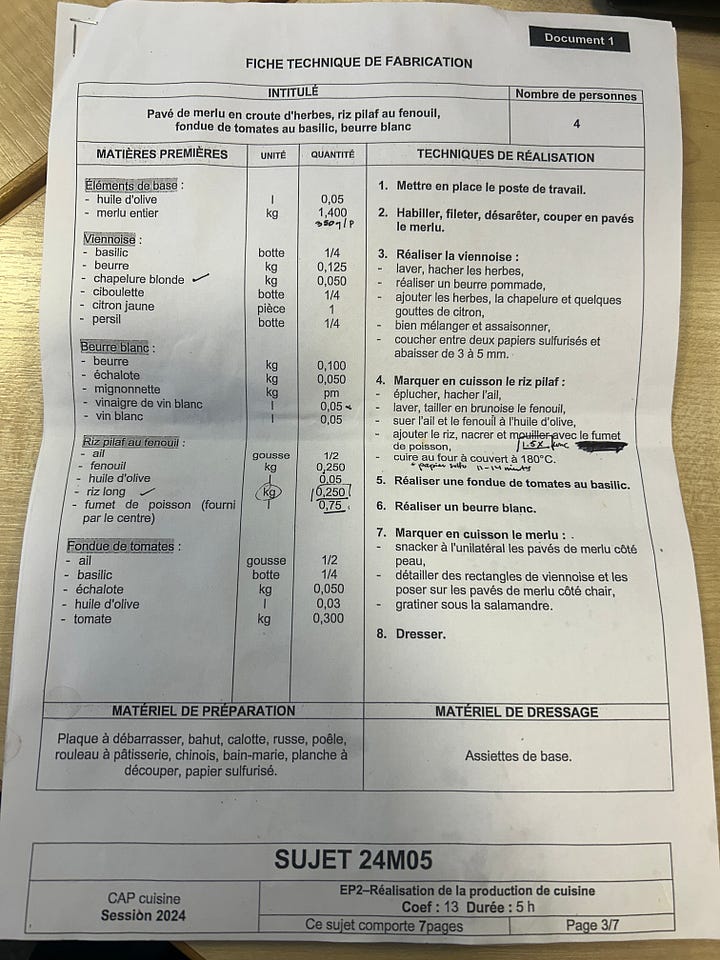

For the main course, I was expected to make 4 servings of hake fish with an herb crust, rice pilaf with fennel, tomato “fondue” (sautéed tomatoes), and beurre blanc sauce. Hake is a white fish, similar to cod in taste and texture, and is very commonly eaten in Europe.

I was immediately overwhelmed when I understood that I had five separate elements to prepare. On top of that, I wasn’t given a recipe or technique for the rice pilaf, the tomatoes, or the beurre blanc, but luckily, I had made them all before in class and had the recipes written in my notebook. Phones are strictly forbidden, of course (which also means no photos, so you’ll have to rely on your imagination here on out!)

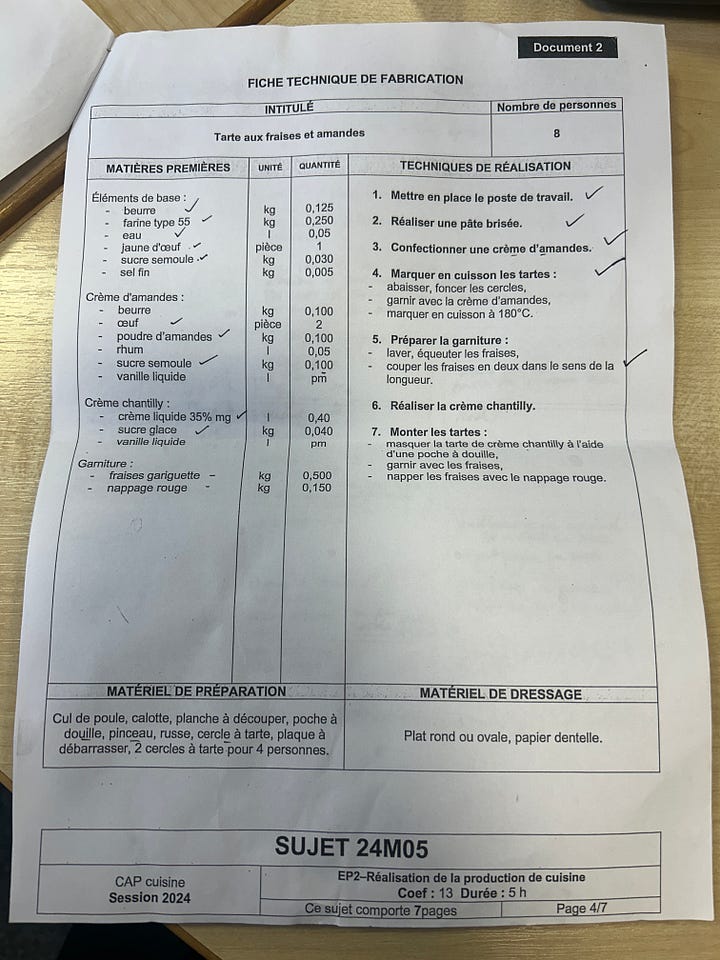

For dessert, I was asked to make strawberry tart for 8 with an almond cream base baked into the crust and whipped cream and strawberries on top. Again, no recipe for the pastry crust or almond cream, which felt very Great British Bake-Off. At first glance, I was fully prepared to make one big tart for 8 people — only when I noticed two platters at my workstation did I understand that I had to make two smaller tarts for 4 people each. Extra work, why not!

Once in the kitchen, I got straight to work making my pastry dough. I let it rest in the fridge while I made almond cream with ground almonds, butter, sugar and eggs. After piping the almond mixture into my tart shells, I threw it in the oven so that I could focus on other things.

Next I had to tackle the fish — best to get the most important thing out of the way.

I had a whole hake fish, which was about 18 inches long. The stomach had been opened and partially cleaned out, but a small langoustine (like a crawfish) was still hiding out inside — a sign that the cleaning job had not been thorough. I trimmed, scaled, and rinsed the fish before slicing off my first fillet.

Once the fish was split in two, I noticed little pieces of seaweed everywhere, especially around the abdomen. I ignored this, telling myself I would rinse the fish again, and started to take off the second fillet. But something possessed me to pick up a few pieces of “seaweed” and rub them between my fingers. To my shock and disgust, the seaweed moved…

IT WAS WORMS!

Or, more specifically, the aforementioned anisakis parasite.

I panicked and called a chef over, who reassured me that I was not going to give anyone food poisoning if I trimmed off every infested piece and cooked it well to kill any stragglers.

Apparently, it’s very common for hake to have this parasite because they are deep-water fish and bottom-feeders, and their thin underbellies make them more susceptible to the worms. Noted. No more hake.

Time was rushing by, and I was in the weeds, as they say.

I threw together a fish stock and chopped my fennal for the rice pilaf, then quickly diced some tomatoes (canned, because it was March) and sautéed them with garlic and basil until the liquid evaporated, making what is called a fondue de tomates. I made an herb crust for my fish with soft butter and breadcrumbs, finely diced chives and parsley, and lemon juice.

I nearly forgot about my tarts, which were golden brown and out of the oven but still missing their whipped cream and strawberries. I somehow found time to whip a cup and a half of heavy cream (by hand), pipe it on top of the baked almond cream, and disperse the strawberries as artfully as possible, which is harder than it sounds when hands are shaking from adrenaline.

At the last minute, I finally cooked my fish, leaving it a bit undercooked on the inside (a calculated risk) because I knew I would put it under the salamander oven to crisp up my herb crust and finish cooking it.

I dressed my plates quickly, using round cookie-cutters to keep my rice and tomatoes as neat as possible. In a blur, they were off to the room next door, where a committee of chefs (including the chefs from our restaurant internships) had volunteered to serve as judges for the day.

With the hard part behind us, our team of 6 cleaned the kitchen and waited to be called next door to receive feedback from two designated chefs.

The first thing they said to me was thanks for the strawberry tarts, to which I replied my pleasure, I’m glad they were good even though it’s a bit early in the season for strawberries. They told me that they helped themselves to second servings, and I told myself this was off to a good start.

I gave my overall impression of how the morning had gone, which was that I was very slow off the starting block and thrown off by my first wormy fish. They said that I didn’t seem to be stressed and seemed to stay organized throughout, which was news to me.

Of course, there was room for improvement — my rice was overcooked because I put too much stock, and the tomato fondue was a bit bitter, but I chalked that one up to the canned tomatoes, which are impossible to de-seed. My beurre blanc sauce was too acidic, and I learned I could filter out the shallots next time to cut down on the bite because the shallots soak up the vinegar.

They saved the biggest compliment for last: the fish was perfectly seasoned and cooked, not dry on the inside but crisp on top, thanks to the herb crust. I really couldn’t have asked for anything more.

I was even more thrilled a few days later when I learned that I’d received an 18/20 grade. I think that the chefs were extremely generous and the real exam won’t be nearly as lenient, but it gave me a much-needed boost of confidence as I prepare for the final.

It’s only fair that I balance out all that talk of parasite-infested fish with something a little bit more pleasant — some classic French desserts!

The week after exams, we learned how to make the perfect trio of desserts that you might find in a Parisian bistro: the millefuille, the Paris-Brest, and Îles Flottantes.

Nothing compares to a perfect millefuille, which translates to “one thousand layers,” and that can only mean one thing — puff pastry. We didn’t make the puff pastry from scratch this time due to time constraints; storebought is perfectly fine.

The secret is that the puff pastry is cooked between two baking sheets, which stops it from rising too much while maintaining a shatteringly crisp texture. Once the pastry is nice and golden, the second secret is to sprinkle powdered sugar all over it before putting it back in the oven, resulting in a caramelized top.

Then, the puff pastry is cut into rectangles, the first layer being topped with dollops of vanilla-infused crème diplomate, which is pastry cream that’s been reinforced with gelatin and lightened with whipped cream. Then, another layer of pastry, then more cream, and a final layer of pastry sprinkled with more powdered sugar.

The millefeille is a relatively simple dessert, especially the vanilla version, but the contrast in textures can’t be beaten. This might have been my favorite dessert we made all year.

Next, we were on to the Paris-Brest, which is a circular choux pastry sprinkled with almonds and cut in half then filled with praline buttercream. The story behind this pastry is that it was created for the bike race that took place between Paris and Brest and back, hence the round shape, like a bike wheel. It’s incredibly rich, said to have enough calories to fuel you for an athletic feat.

This pastry was a bit more technical, requiring a good choux pastry that’s airy and light on the inside but a bit crisp on the outside. The hardest part was piping the thick buttercream to make upright loops, which takes some practice. My slightly wonky buttercream loops still tasted delicious.

We completed the trifecta of French bistro desserts with Îles Flottantes, or floating islands, which are soft meringues that have been poached in milk and water. They look a lot like islands when they’re being cooked and they’re always served on a pool of custard, hence their name. We whipped our meringues by hand to really earn it, then floated them in custard and drizzled them with caramel and almonds. And it certainly paid off — floating islands are like eating a cloud.

It was really fun to get to recreate these iconic desserts that I’ve tasted countless times over the years in restaurants and pastry shops — but never like this. While all are relatively simple French desserts with only two main elements each, their simplicity allows the technique and quality of the ingredients to shine through. They taste so much better when you make them yourself; I’m not sure I’ll be able to go back.

Until next time!

Bisous,

Monique

Bravo, de nouveau !!!

Good job Monique 👩🍳